So, how does writing and editing comics help you when it comes to screenwriting? British comics scribes are good at pithy, thanks to their on-the-job training [see last post]. Satire and irony are almost pre-requisites for the job on this side of the Atlantic, along with a dark sense of humour and plenty of cynicism. Having been raised a Catholic is another common denominator, but not obligatory - still, it is surprising how many British comics writers have that little reservoir of guilt, self-loathing and lust running their work. Phillip Larkin once wrote that 'They fuck you up, your mum and dad...' Well, the Catholic Church has it moments too. Fortunately for writers, that's all good fuel for the fire, grist for the mill and raw matter for the cliche generator.

Comics writers - for the most part - have a good grasp of characterisation, motivation and can plot their way out of anything. If they write full script [as opposed to the plot-first method pioneered by Marvel - not a good choice for conversion to TV or filmmaking, IMHO], they already write stories in a format remarkably similar to screenplays.

Most importantly of all, comics writers are used to collaborating. They are not the end of the chain, they are not the god of their domain [much as some would like to be]. They write a script and then it is given to the next person in the process. Sometimes that's a penciller, sometimes it's an illustrator who does completed black line art and sometimes the artist even paints or colour his work too. I think Dave Gibbons is almost the only British artist who also frequently letters his own work, for that extra level of control over his work.

In comics, the writer-artist is the auteur - far more so than the theory that a film director is an auteur. Excuse me for slipping into rant mode, but what a load of bollocks. An author writes a book. Aside from the editor [and copy editor and the occasional muppet in the production process who decides to tinker or whose mind wanders], the book author has a direct linkage into the thoughts, mind and imagination of their reader. That, to me, is a true auteur. A film director is a guy who depends upon anywhere from between five and five hundred other creative individuals to help him achieve something resembling his vision. He's the auteur of the film? My arse. End rant mode.

So, like I was saying several paragraphs ago [my, I do digress, don't I? Yes, you do, now shut up and type], comics scribes are used to be part of the process. An important part, a major cog in the creative machine, but still only one moving part. That's good training for how they'll be treated if they ever somehow become screenwriters. In cinema, infamously, writers are paid first but frequently come last when respect is being given. Television is another matter, of course. In the US, the showrunner is far more powerful a figure, but then they have responsibilities that extend far beyond merely writing the damn show [or even simply supervising the writing - and rewriting and rewriting and rewriting - of the show]. Like the name implies, they run the show - aided and abetted by an army of production staff.

The showrunner method is slowly creeping across the Atlantic, bringing with it the writers' room system of breaking a story in a group environment, asystem that can design a horse that looks like a thoroghbred, and not like a camel. [You want to see a writers' room in action? Check out the documentary on the R1 DVD release of The Shield Season 3 - inspiring stuff.]

Gotta say, I would love to be writing in such an environment. The reality would, no doubt, be something of a shock to the system but some of my most enjoyable writing expereiences have been where I've collaborated with another person - thrown ideas around and come up with something better, something the two of us wouldn't have found on our own.

Gotta say, I would love to be writing in such an environment. The reality would, no doubt, be something of a shock to the system but some of my most enjoyable writing expereiences have been where I've collaborated with another person - thrown ideas around and come up with something better, something the two of us wouldn't have found on our own.2005's example of a showrunner driving a great British show was Russell T Davies [in collaboration with Julie Gardner and Phil Collinson] resurrecting Doctor Who. RTD wrote the series bible, provided the writer's vision and communicated that vision to the other scribes. And it worked. The BBC has also employed that system on Merlin with Chris Chibnall, although the project has apparently not been greenlight for production. Shame, I was looking forward to seeing it.

Anyway, like I said, comics scribes are primed for screenwriting for all the above reasons and more. They're a fount of ideas, [you have to be, comics eat content like crazy] fast and pithy.

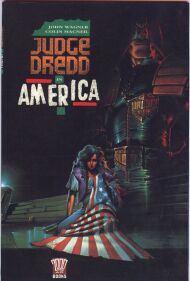

However, let's be honest - most comics are superficial and so are the scripts. Action, plot mechanics, well-carpentered structure - not a problem. Sub-text, themes, image systems - these things are not so important when you're writing cape fiction. How will Superblooperman escape certain death, rescue his girlfriend/boyfriend/poodle and save the world - that's important. There's probably an argument to be made that the best cinematic adaptations of comics have been where the material has a strong, underlying sub-text and thematic content. X-Men: mutants as outsiders, the dangers of prejudice, fear of the unknown, all that stuff. A History of Violence: a graphic novel with a lot to say about the masks people wear, the roles they assume, the importance of family, the impact of violence - all big, meaty stuff. Probably the best Dredd story is a 62-pager called America, by John Wagner and Colin MacNeil.

Dripping with subtext and thematic material. If only that had been the Dredd movie, not the mashup of Judge Cal and the Return of Rico that got released in '95. Such is life.

Dripping with subtext and thematic material. If only that had been the Dredd movie, not the mashup of Judge Cal and the Return of Rico that got released in '95. Such is life. The lack of depth in comics writing probably explains why the comics work of Alan Moore has been so ripe for cinema adaptation: From Hell, V For Vendetta. League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Constantine and the list goes on. Heaven help us, someday someone may actually turn Watchmen into a film - the fools. It's a mini-series, not a movie! Moore's work has a depth and richness that bedazzles when put next to the average comic book.

It's no surprise so few comics writers haven't cracked the shift to TV or film writing. I struggle to think of many examples. In fact I'm struggling to think of any examples. Neil Gaiman. Si Spencer. Pete Milligan.

But what about the other way? What about the post-Millennium influx of screenwriters into comics? Are they just slumming it, picking up some easy money writing down for the fanboys? Are they just scratching a childhood itch to write Wolverine or the Batman or some other bruiser in tights and a cape? Or is there something else at work here?

All may - or may not - be revealed next time, in Part III.

No comments:

Post a Comment